In the mid-19th century, Victorian society found itself at a crossroads. Science was accelerating—with inventions like the telegraph and discoveries like evolution—yet traditional religious views were being challenged like never before. Into this charged atmosphere entered spiritualism, the belief that the living could communicate with the spirits of the dead. It wasn’t just a fringe idea; it became a cultural phenomenon that gripped both the common people and the elite.

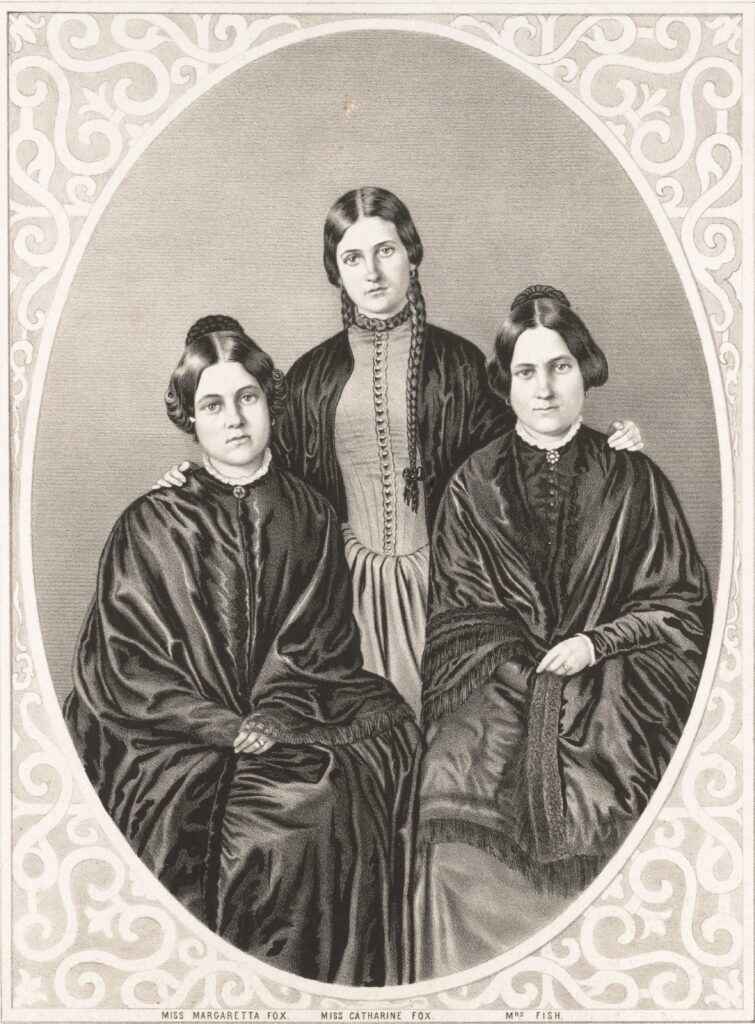

The movement officially sparked in 1848 when the Fox sisters of New York claimed to communicate with a spirit through mysterious “rappings” in their home. Their sensational story spread rapidly, inspiring public séances, spirit photography, and the rise of professional mediums across both America and Britain. Parlor rooms across England became filled with hopeful seekers, dark curtains, levitating tables, and whispered messages from the beyond.

What made Victorian spiritualism especially fascinating was how it straddled the line between faith and reason. Scientific investigations into mediumship were not uncommon. Figures like Sir William Crookes, a respected chemist and physicist, conducted studies on famous mediums such as Daniel Dunglas Home. Crookes claimed to have observed real phenomena—objects moving without human touch, ghostly forms materializing—using what he considered rigorous methods.

Other prominent thinkers, including Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer of natural selection, defended spiritualism publicly, believing it offered scientific proof of an afterlife. Wallace argued that psychic abilities were natural extensions of human evolution, a progressive step in humanity’s spiritual journey.

At the same time, skeptics waged war on fraudulent practices. Harry Houdini, the famed illusionist, made it a personal mission to expose mediums who used tricks like hidden wires, ventriloquism, and sleight of hand. Scientists such as Thomas Huxley outright dismissed spiritualism as wishful thinking dressed up in the language of pseudo-science.

Despite the growing body of debunking evidence, spiritualism offered something deeper than proof: hope. In a time when disease and early death were commonplace, and loved ones could vanish in an instant, spiritualism provided emotional solace. It suggested that death was not an end but a transformation—that the soul continued its journey, reachable with patience, sincerity, and the right medium.

Today, Victorian spiritualism is a fascinating chapter in the ongoing human story—a testament to our need to blend wonder with reason, to search for answers that satisfy both the heart and the mind.

Spirit photography became wildly popular in the Victorian era. Photographers like William Mumler claimed to capture images of ghostly figures standing beside the living—though many were later exposed as clever double exposures.

Queen Victoria herself was fascinated by spiritualism. After the death of Prince Albert, she reportedly consulted mediums in an effort to communicate with her beloved husband.

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) was founded in 1882 by scientists and scholars dedicated to rigorously investigating paranormal phenomena without bias—a group that still exists today!

Séances often used early “technology” like the planchette (a forerunner of the Ouija board) to “help spirits spell out messages” to the living.